Vision

For over forty years, computation has centered about machines, not people. We

have catered to expensive computers, pampering them in air-conditioned rooms or

carrying them around with us. Purporting to serve us, they have actually

forced us to serve them. They have been difficult to use. They have required

us to interact with them on their terms, speaking their languages and

manipulating their keyboards or mice. They have not been aware of our needs or

even of whether we were in the room with them. Virtual reality only makes

matters worse: with it, we do not simply serve computers, but also live in a

reality they create.

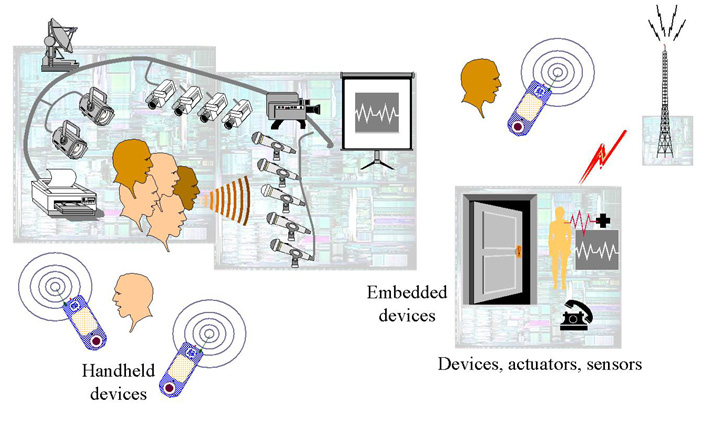

In the future, computation will be human-centered. It will be freely available everywhere, like batteries and power sockets, or oxygen in the air we breathe. It will enter the human world, handling our goals and needs and helping us to do more while doing less. We will not need to carry our own devices around with us. Instead, configurable generic devices, either handheld or embedded in the environment, will bring computation to us, whenever we need it and wherever we might be. As we interact with these "anonymous" devices, they will adopt our information personalities. They will respect our desires for privacy and security. We won't have to type, click, or learn new computer jargon. Instead, we'll communicate naturally, using speech and gestures that describe our intent ("send this to Hari" or "print that picture on the nearest color printer"), and leave it to the computer to carry out our will.

New systems will boost our productivity. They will help us automate repetitive human tasks, control a wealth of physical devices in the environment, find the information we need (when we need it, without forcing our eyes to examine thousands of search-engine hits), and enable us to work together with other people through space and time.

Challenges

To support highly dynamic and varied human activities, the Oxygen system must

master many technical challenges. It must be

- pervasive—it must be everywhere, with every portal reaching into the same information base;

- embedded—it must live in our world, sensing and affecting it;

- nomadic—it must allow users and computations to move around freely, according to their needs;

- adaptable—it must provide flexibility and spontaneity, in response to changes in user requirements and operating conditions;

- powerful, yet efficient—it must free itself from constraints imposed by bounded hardware resources, addressing instead system constraints imposed by user demands and available power or communication bandwidth;

- intentional—it must enable people to name services and software objects by intent, for example, "the nearest printer," as opposed to by address;

- eternal—it must never shut down or reboot; components may come and go in response to demand, errors, and upgrades, but Oxygen as a whole must be available all the time.

Approach

Oxygen enables pervasive, human-centered computing through a combination of

specific user and system technologies. Oxygen's user technologies directly

address human needs. Speech and vision technologies

enable us to communicate with Oxygen as if we're interacting with another

person, saving much time and effort. Automation,

individualized knowledge access, and collaboration technologies help us perform a wide

variety of tasks that we want to do in the ways we like to do them.

Oxygen's device, network, and software technologies dramatically extend our range by delivering user technologies to us at home, at work or on the go. Computational devices, called Enviro21s (E21s), embedded in our homes, offices, and cars sense and affect our immediate environment. Handheld devices, called Handy21s (H21s), empower us to communicate and compute no matter where we are. Dynamic, self-configuring networks (N21s) help our machines locate each other as well as the people, services, and resources we want to reach. Software that adapts to changes in the environment or in user requirements (O2S) help us do what we want when we want to do it.

Oxygen device technologies

Devices in Oxygen supply power for computation, communication, and perception

in much the same way that batteries and wall outlets supply power for

electrical appliances. Both mobile and stationary devices are universal

communication and computation appliances. They are also anonymous: they do not

store configurations that are customized to any particular user. As for

batteries and power outlets, the primary difference between them lies in the

amount of energy they supply.

Collections of embedded devices, called E21s, create intelligent spaces inside offices, buildings, homes, and vehicles. E21s provide large amounts of embedded computation, as well as interfaces to camera and microphone arrays, large area displays, and other devices. Users communicate naturally in the spaces created by the E21s, using speech and vision, without being aware of any particular point of interaction.

Handheld devices, called H21s, provide mobile access points for users both within and without the intelligent spaces controlled by E21s. H21s accept speech and visual input, and they can reconfigure themselves to support multiple communication protocols or to perform a wide variety of useful functions (e.g., to serve as cellular phones, beepers, radios, televisions, geographical positioning systems, cameras, or personal digital assistants). H21s can conserve power by offloading communication and computation onto nearby E21s.

Initial prototypes for the Oxygen device technologies are based on commodity hardware. Eventually, the device technologies will use Raw computational fabrics to increase performance for streaming computations and to make more efficient use of power.

Oxygen network technologies

Networks, called N21s, connect dynamically changing

configurations of self-identifying mobile and stationary devices to form

collaborative regions. N21s support multiple communication protocols for

low-power point-to-point, building-wide, and campus-wide communication. N21s

also provide completely decentralized mechanisms for naming, location and

resource discovery, and secure information access.

Oxygen software technologies

The Oxygen software environment is built to support

change, which is inevitable if Oxygen is to provide a system that is adaptable,

let alone eternal. Change is occasioned by anonymous devices customizing to

users, by explicit user requests, by the needs of applications and their

components, by current operating conditions, by the availability of new

software and upgrades, by failures, or by any number of other causes. Oxygen's

software architecture relies on control and planning abstractions that provide

mechanisms for change, on specifications that support putting these mechanisms

to use, and on persistent object stores with transactional semantics to provide

operational support for change.

Oxygen perceptual technologies

Speech and vision, rather

than keyboards and mice, provide the main modes of interaction in Oxygen.

Multimodal integration increases the effectiveness of these perceptual

technologies, for example, by using vision to augment speech understanding by

recognizing facial expressions, lip movement, and gaze. Perceptual

technologies are part of the core of Oxygen, not just afterthoughts or

interfaces to separate applications. Oxygen applications can tailor

"lite" versions of these technologies quickly to make human-machine

interaction easy and natural. Graceful interdomain context switching supports

seamless integration of applications.

Oxygen user technologies

Several user technologies harness Oxygen's massive computational,

communication, and perceptual resources. They both exploit the capacity of

Oxygen's system technologies for change in support of users, and they help

provide Oxygen's system technologies with that capacity. Oxygen user

technologies include:

- Automation technologies, which offer natural, easy-to-use, customizable, and adaptive mechanisms for automating and tuning repetitive information and control tasks. For example, they allow users to create scripts that control devices such as doors or heating systems according to their tastes.

- Collaboration technologies, which enable the formation of spontaneous collaborative regions that accommodate the needs of highly mobile people and computations. They also provide support for recording and archiving speech and video fragments from meetings, and for linking these fragments to issues, summaries, keywords, and annotations.

- Knowledge access technologies, which offer greatly improved access to information, customized to the needs of people, applications, and software systems. They allow users to access their own knowledge bases, the knowledge bases of friends and associates, and those on the web. They facilitate this access through semantic connection nets.

Applications

The following scenarios illustrate how Oxygen's integrated technologies make it

easier for people to do more by doing less, wherever they may be.

Business conference

Hélène calls Ralph in New York from their company's home office in Paris.

Ralph's E21, connected to his phone, recognizes Hélène's telephone number; it

answers in her native French, reports that Ralph is away on vacation, and asks

if her call is urgent. The E21's multilingual speech and automation systems,

which Ralph has scripted to handle urgent calls from people such as Hélène,

recognize the word "décisif" in Hélène's reply and transfer the call to Ralph's

H21 in his hotel. When Ralph speaks with Hélène, he decides to bring George,

now at home in London, into the conversation.

All three decide to meet next week in Paris. Conversing with their E21s, they ask their automated calendars to compare their schedules and check the availability of flights from New York and London to Paris. Next Tuesday at 11am looks good. All three say "OK," and their automation systems make the necessary reservations.

![]() Ralph and George arrive at Paris headquarters. At the front desk, they pick up

H21s, which recognize their faces and connect to their E21s in New York and

London. Ralph asks his H21 where they can find Hélène. It tells them she's

across the street, and it provides an indoor/outdoor navigation system to guide

them to her. George asks his H21 for "last week's technical

drawings," which he forgot to bring. The H21 finds and fetches the

drawings just as they meet Hélène.

Ralph and George arrive at Paris headquarters. At the front desk, they pick up

H21s, which recognize their faces and connect to their E21s in New York and

London. Ralph asks his H21 where they can find Hélène. It tells them she's

across the street, and it provides an indoor/outdoor navigation system to guide

them to her. George asks his H21 for "last week's technical

drawings," which he forgot to bring. The H21 finds and fetches the

drawings just as they meet Hélène.

Guardian Angel

Jane and her husband Tom live in suburban Boston and cherish their

independence. As they have advanced in age, they have acquired a growing

number of devices and appliances, which they have connected to their E21. They

no longer miss calls or visitors because they cannot get to the telephone or

door in time; microphones and speakers in the walls enable them to answer

either at any time. Sensors and actuators in the bathroom make sure that the

bathtub does not overflow and that the water temperature is neither too hot nor

too cold. Their automated knowledge system keeps track of which television

programs they have enjoyed and alerts them when similar programs will be shown.

Just before their children moved away from the area, Jane and Tom enhanced their H21 to provide them with more help. Tom uses the system now to jog his memory by asking simple questions, such as "Did I take my medicine today?" or "Where did I put my glasses?" The E21's vision system, using cameras in the walls, recognizes and records patterns in Tom's motion. When Tom visits his doctor, he can bring along the vision system's records to see if there are changes in his gait that might indicate the onset of medical problems. Jane and Tom can also set up the vision system to contact medical personnel in case one of them falls down when alone. By delivering these ongoing services, the E21 affords peace of mind to both parents and children.

Oxygen today

Oxygen technologies are entering our everyday lives. Following are some of the

technologies being tested at MIT and by the Oxygen industry partners.

Oxygen device technologies

![]() A prototype H21 is equipped with a microphone,

speaker, camera, accelerometer, and display for use with perceptual interfaces. RAW and Scale expose

hardware to compilers, which optimize the use of circuitry and power. StreamIt provides a language and optimizing

compiler for streaming applications.

A prototype H21 is equipped with a microphone,

speaker, camera, accelerometer, and display for use with perceptual interfaces. RAW and Scale expose

hardware to compilers, which optimize the use of circuitry and power. StreamIt provides a language and optimizing

compiler for streaming applications.

Oxygen network technologies

![]() The Cricket location support system provides an

indoor analog of GPS. The Intentional Naming

System (INS) provides resource discovery based on what services do, rather

than on where they are located. The Self-Certifying

(SFS) and Cooperative (CFS) File Systems

provide secure access to data over untrusted networks without requiring

centralized control.

The Cricket location support system provides an

indoor analog of GPS. The Intentional Naming

System (INS) provides resource discovery based on what services do, rather

than on where they are located. The Self-Certifying

(SFS) and Cooperative (CFS) File Systems

provide secure access to data over untrusted networks without requiring

centralized control.

![]() Trusted software proxies provide secure,

private, and efficient access to networked and mobile devices and people.

Decentralization in Oxygen aids privacy: users can locate what they need

without having to reveal their own location.

Trusted software proxies provide secure,

private, and efficient access to networked and mobile devices and people.

Decentralization in Oxygen aids privacy: users can locate what they need

without having to reveal their own location.

Oxygen software technologies

![]() GOALS is an architecture that enables

software to adapt to changes in user locations and needs, respond both to

component failures and newly available resources, and maintain continuity of

service as the set of available resources evolves. GOALS is motivated, in

part, by experience gained with MetaGlue,

a robust architecture for software agents.

GOALS is an architecture that enables

software to adapt to changes in user locations and needs, respond both to

component failures and newly available resources, and maintain continuity of

service as the set of available resources evolves. GOALS is motivated, in

part, by experience gained with MetaGlue,

a robust architecture for software agents.

Oxygen perceptual technologies

![]() Multimodal systems enhance recognition of

both speech and vision. Multilingual

systems support dialog among participants speaking different languages. The SpeechBuilder utility supports development

of spoken interfaces. Person tracking, face, gaze, and gesture recognition

utilities support development of visual interfaces. Systems that understand

sketching on whiteboards provide more natural interfaces to traditional

software packages.

Multimodal systems enhance recognition of

both speech and vision. Multilingual

systems support dialog among participants speaking different languages. The SpeechBuilder utility supports development

of spoken interfaces. Person tracking, face, gaze, and gesture recognition

utilities support development of visual interfaces. Systems that understand

sketching on whiteboards provide more natural interfaces to traditional

software packages.

Oxygen user technologies

![]() Haystack and the Semantic Web support personalized

information management and collaboration through metadata management and

manipulation. ASSIST helps extract

design rationales from simple sketches.

Haystack and the Semantic Web support personalized

information management and collaboration through metadata management and

manipulation. ASSIST helps extract

design rationales from simple sketches.

![]() The Intelligent Room is a highly

interactive environment that uses embedded computation to observe and

participate in normal, everyday events, such as collaborative meetings.

The Intelligent Room is a highly

interactive environment that uses embedded computation to observe and

participate in normal, everyday events, such as collaborative meetings.

True innovation in Oxygen comes from MIT students, researchers, and others using Oxygen technologies and systems for their daily work. Hence Project Oxygen is building a system to use, and using it to build.